What a land Piemonte is.

Hemmed-in by majestic peaks, the Piemontese people settled like marbles in a bowl, making the best of what they found around them. And what riches they found: snow-covered mountains and shimmering lakes; alpine meadows suitable for producing the most sublime cheese – and for losing a few hours in the contemplation of the land; flat plains to grow bountiful produce and livestock. And between these last two, hillsides where altitude, aspect and soil composition came together to give land utterly unsuitable for agriculture.

But not for viticulture; indeed, the foothills of the Alps – the pedemontana – could almost have been formed with grapevines in mind.

PIEMONTESE WINE – REGIONS & GRAPES

When the Greeks colonised the southern Italian peninsula from the 8th century BC, they called it Enotria – the land of the grapevines. Though conditions in Puglia were quite different to Piemonte, those ancients were onto something, for every region in Italy produces wine. And those altitudes, aspects and soils found in the hills of Piemonte give rise to some of the greatest wines in the world.

Here we will begin to look at them, starting with the principal regions and grape varieties of Piemonte.

Viticultural Piemonte

Like every other region in Italy, Piemonte not only has its own cuisine (we don’t eat pesto – that’s from Liguria…) but its own wines which, you will not be surprised to learn, go very well with the food.

The wines in Piemonte are identified by region and/or grape variety. All classifications above Table Wine – labelled Vino Rosso, Vino Bianco or Vino Rosato depending on the colour – have strict rules based upon geography (i.e.: where they are grown and made) and production. The geographical element includes what grape varieties you can use; the production element, what you are allowed to, or have to, do with them once you’ve picked them.

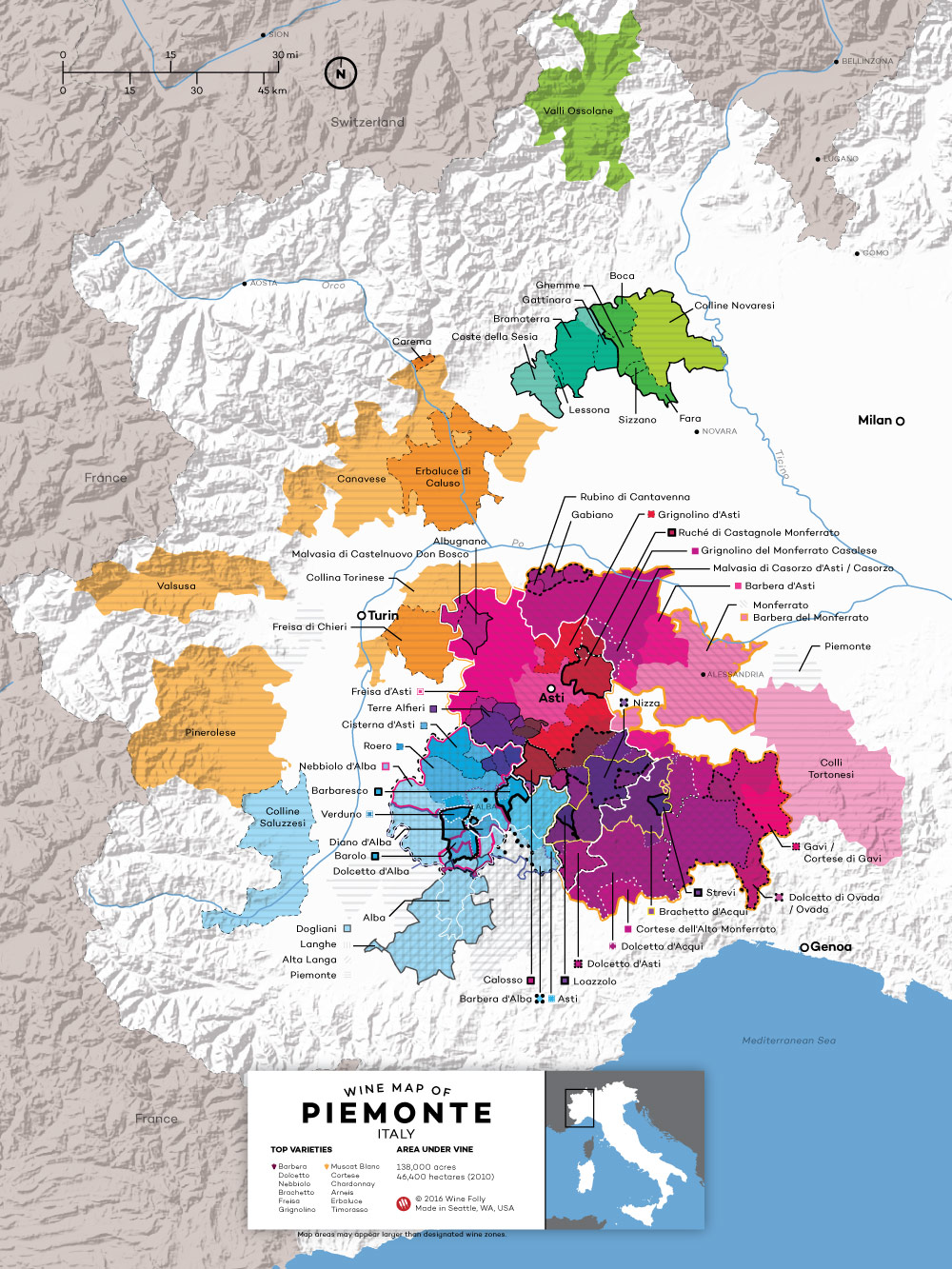

Let’s start with the Regions. As you can see from the map, there are plenty of them, so strap yourself in because we’re in for a long one…

The map is reproduced with kind permission of Wine Folly, who did a far better job with the map than I would, and have their own excellent guide to the wines of Piemonte!

Principal Regions

LANGHE – Centred around Alba and within which are the 2 most highly regarded regions of Barolo and Barbaresco. ‘Alba’ is also a denomination for wines such as Barbera and Nebbiolo (our 2 main grape varieties along with Dolcetto). Myriad grape varieties are allowed in the Langhe denomination. This is not the largest growing region in terms of production, but it is the standard-bearer in terms of the international reputation of Piemonte.

The Langhe region is located on the south side of the river Tanaro and abuts the Monferrato to the east and stretches down to the Ligurian border to the south. Also located within the Langhe are Diano and Dogliani – 2 D.O.C.G.s for Dolcetto wines – and, much further east, Ovada, also Dolcetto. Then there is the Alta Langa region, which, naturally, falls both within and outside the geographical Langhe.

ROERO – On the other, northern, side of the river Tanaro, this is predominantly a white wine region, mainly based on the Arneis grape. Good reds are also made here from Barbera, Nebbiolo, Dolcetto and so on.

MONFERRATO – Butting up against the Langhe and Roero, this is Barbera’s heartland. It has much more than just that to offer, though: excellent white wines from local and international varieties, fizz and reds not only from Barbera, but other local specialities such as Ruchè and Grignolino.

ASTI – Known probably through Asti Spumante ‘fame’, Barbera and Moscato thrive here. A large appellation with some great wines. And Asti ‘Spumante’.

GAVI – This is almost in Liguria, and is Piemonte’s best-known white wine, made only from Cortese grapes.

These are the regions with the most exposure internationally, which is why I have put them under the ‘principal’ banner. There are many other regions making good-to-exceptional wines, but in small quantities, which are much less recognisable overseas. They each have their grapes, microclimates, soils and production methods. And they are all worth looking out for – after all you should try anything once, and much more than that if you like it. Some of these regions are listed below:

GATTINARA – We are north of Turin here, in Alto Piemonte. In quality terms, it’s important, and was often considered superior to Barolo in centuries past, but in production terms it’s tiny, so it goes here. Based on minimum 90% Nebbiolo.

GHEMME – Another Alto Piemonte region. Minimum 85% Nebbiolo, 34 months ageing, of which at least 18 must be in wood.

ERBALUCE DI CALUSO – Based on the ancient white Erbaluce grape, grown north of Torino around Caluso.

CAREMA – Also in Alto Piemonte. Minimum 85% Nebbiolo, 2 years’ ageing of which at least 12 months in wood.

COLLI TORTONESI – The Easternmost region in Piemonte, around Tortona. A number of different wines are made here, but the region is notable especially for its white Timorasso wines, which can be really excellent.

And there are loads of others. I would recommend books such as The World Atlas of Wine, From Barolo to Valpolicella, The Native Wine Grapes of Italy and Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs to find out more. For online options, try Italian Wine Central and Wine Folly.

Principal Grape Varieties

Well, you can’t very well have a wine region without grapes (no matter what the pineapple wine producers of Hawaii might say). So here are some of the lovely choices we have available to us:

NEBBIOLO – The grape of Piemonte. This black grape is an ancient native of Piemonte, with the first documented mention of it being in 1266. It is the basis for (almost) all the greatest red wines in Piemonte – Barolo, Barbaresco, Roero, Gattinara, Ghemme, Lessona and so on, as well as Nebbiolo d’Alba and Langhe Nebbiolo. It is also a star in Valtellina, in northern Lombardy, right up under the Swiss border. Internationally, it is grown in Argentina, Australia and the USA, among other places, but does not have the international presence of the ubiquitous French varieties.

It is a vigorous variety and is fairly easy to grow, provided the soil is right – it is not pernickety like Pinot Noir or Dolcetto – with generally compact bunches of small grapes with thick, tannic skins. It is the first variety to bud in spring, and the last to ripen in autumn. It may be a parent of Friesa – or the other way around – which makes it likely that it is a cousin of Viognier, would you believe?

BARBERA – The Other grape of Piemonte, if you’re talking about quantity. The most widely-planted grape in the region, grown all over Piemonte, but most associated with the red wines of the Asti and Monferrato regions. This was not always the case – it only came to dominate vineyard acreage in Piemonte after Phylloxera struck in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Barbera is the engine-room of production in Piemonte, but is also grown beyond the region’s borders: around 40% of Italy’s Barbera is grown outside Piemonte. It crops up overseas in much the same sort of places as Nebbiolo: Australia, Argentina, the USA. Larger bunches of generally easy-to-grow grapes with plenty of colour and acidity but almost no tannin.

DOLCETTO – More of a Langhe variety than an Asti one, the everyday red wine drink around Alba. Of the three principal grapes of the Langhe, Dolcetto sits somewhere in between Nebbiolo and Barbera in terms of its tannins, acidity and colour.

It has been around the Langhe, and specifically in one of its heartlands – Dogliani – since at least 1593. It is an early-ripening variety, but very fussy in the vineyard: it can sometimes simply drop fruit if it doesn’t like the conditions.

Outside Piemonte, there is some in Liguria and a couple of other minor outposts, and a sprinkling in the USA, Australia and Argentina. Mas de Daumas Gassac in southern France used to have 0.1 hectares (0.25 acres), but I don’t know if they still do.

ARNEIS – Alba’s white grape of choice, it is grown mainly north of the river in the Roero. It was possibly first mentioned in 1432, so it has been around a while. It is a vigorous variety and ripens around the same time as Dolcetto – mid-September-ish (though these things are changing – how long before our ‘ripened earlier than the average’ will become the new average…?). Outside Piemonte, there is some in Liguria, which makes sense geographically, and some in Sardegna, which makes sense historically. As with the others mentioned above, there is some in Australia and the USA, and a little in New Zealand.

CORTESE – The white grape of Gavi, this has been in south-eastern Piemonte for at least 400 years. Thing is, I don’t know why, given it’s so bland. It was originally planted to supply the fish restaurants of Liguria, and its acidity does at least pair well. I’m being a bit unfair here, really – it can make some really nice wines, and works well in sparklers, too. It’s just not the last word in character.

MOSCATO – Responsible for Asti (formerly Asti Spumante) Moscato d’Asti, some dry, still white wines and some dessert wines called Moscato Passito.

Now then, you want an ancient variety? Moscato probably originated in Greece before being more widely distributed in Europe by the Romans after the Greeks brought it to ‘Enotria’. On the other hand, it may have originated in Italy, where in any case it has lived for centuries, and spawned many offspring. A sort of vinous Silvio Berlusconi.

In Piemonte, it is used primarily to make our frothy sweet wines, but it is also becoming fashionable to make it dry as it is in Alsace, for example, or Iberia. It buds early, ripens early here and is a very aromatic grape.

If you want to know where it’s grown, it would be easier to list places where it isn’t…! All over Europe it is to be found making delicious dry, off-dry and sweet wines. And this continues outside Europe’s borders – North and South America, Australia and New Zealand, and it has been in South Africa since at least the 1700s and perhaps as early as 1659.

Pedigree.

There is also a plethora of other grapes that can be terrific but, due to the quantities produced, are not so well-known:

TIMORASSO – Great white grape grown around Tortona. Piemonte’s leading Irish grape variety (think about it) is another with regional roots going back centuries – it may have been mentioned in 1209, but in any case is a long-time resident of Tortona. Prior to Phylloxera, Timorasso was widespread in the province of Alessandria, but Cortese, bland but more biddable, won out afterwards. Timorasso was almost lost in the 1970s and 1980s until a fella by the name of Walter Massa vinified a 100% Timorasso (the story I heard was that it was always used as part of a field blend rather than on its own, but a local grappa producer wanted to make a varietal grappa from it, so she asked Walter Massa if he could make a varietal wine from it. He did and was very pleasantly surprised by the quality of the results.)

It is a vigorous variety and ripens early, giving low yields and plenty of sugar. With the warmer average growing seasons of the past 20 years or so, acidity is something to look out for – the grapes can come in a bit low on freshness. But the wines are worth trying and can age very well into something with a hint of old Hunter Valley Semillon.

ERBALUCE – Very interesting white variety grown north of Torino, and making some terrific sweet wines as well as still and fizz.

NASCETTA – Commonly held to be the Langhe’s only native white variety, it was widely regarded and planted between Alba and Mondovì in times gone by, before falling out of favour. It was essentially rescued in 1994 by Elvio Cogno , who made a tiny amount of varietal wine. Today, cultivation is centred around the village of Novello in the Barolo region. The wines are well worth seeking out, with straw and honey overtones, hints of exotic fruit and often dried herb characteristics coming through.

ROSSESE BIANCO – Right, now it gets a bit confusing. Rossese Bianco di Monforte, a very rare variety grown, as the name suggests, in Monforte d’Alba in the Barolo region, is possibly the other whtie native to the Langhe. Giovanni Manzone and Josetta Saffirio both make a varietal wine from this grape (I believe – Josetta Saffirio’s Rossese Bianco could be a Rossese Bianco as opposed to Rossese Bianco di Monforte, though I think it is the latter…) and they are very good. We have Giovanni Manzone to thank for saving this variety. However, in Serralunga d’Alba, Cantine Gemma makes a 100% Rossese Bianco, not a Rossese Bianco di Monforte, but I can’t find out anywhere whether these are distinct varieties or the same one – no-one seems to have done a DNA analysis to find out. Anyway, they’re worth trying.

FREISA – Freisa and Nebbiolo have a parent-offspring relationship. Intriguingly, Freisa looks like it has a close genetic link to Viognier meaning that Nebbiolo and Viognier could be cousins. Whatever further research reveals, Freisa is an ancient Piemontese variety. It is primarily cultivated in the Cuneo, Asti and Torino provinces. Generally a less polished black grape than Nebbiolo it was often made frizzante – and in the Monferrato it still is. Can be delicious.

RUCHÈ – Another local rarity enjoying a bit of a comeback. Very perfumed black grape giving interesting and potentially excellent wines, mainly from around Casale Monferrato, where it almost certainly originated back in the mists of time. I went to a dinner hosted by a producer some years ago and they paired their Ruchè with mature goats’ cheese, which I don’t go for (it smells of the goat, not the cheese, and the goat seems to have been to the toilet about 2 weeks prior without bothering to clean itself in the interim). I couldn’t stop eating the cheese with the Ruchè.

It has a dark colour, a very heady aroma which can lull you into thinking it will be sweet, and some tannin. Definitely one to try.

GRIGNOLINO – Like Ruchè, its origin is in the Monferrato Casalese’s medieval past, or beyond. A black grape that gives almost rosé wines of usually lighter alcohol (though I tried one at 16% recently) it has a softly herbaceous, floral character, reasonable acidity and some tannin. Get an unoaked one, chill it lightly in the summer, drink it outside with friends and Robert is your avuncular relative.

PELAVERGA – A local of Verduno in the Barolo region, this is a black grape giving pink wines. This is another that has plenty of character and will take a chill before giving delicious drinking in warmer weather. I know an importer in the UK, and they sell to the wine bar beneath them – it flies out during the summer.

The wine is usually a little higher in alcohol than you might think, and is overwhelmingly reminiscent of over-ripe strawberries and ground pepper. Find one, stick it in an ice bucket and give it a whirl – you know you want to.

Again, there are others still – and the same rule applies to the regions above: if you see them, try them at least once!

Plus we have the usual international brigade: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Syrah, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Riesling, little bits and bobs of other stuff. But since they’re not from around here, you’ll have to find out about them elsewhere…

So that’s a bit more about the regions and grapes of Piemonte – I hope it’s been informative. Click here for more information about the wines themselves.

In the end, of course, the best way to understand is to visit the regions, see the vineyards and try the wines for yourself!

Come and Visit piemonte

If you’re interested in doing that contact me on evan@piemontemio.com and check out these pages to see how you can get here and what awaits you once you have arrived!